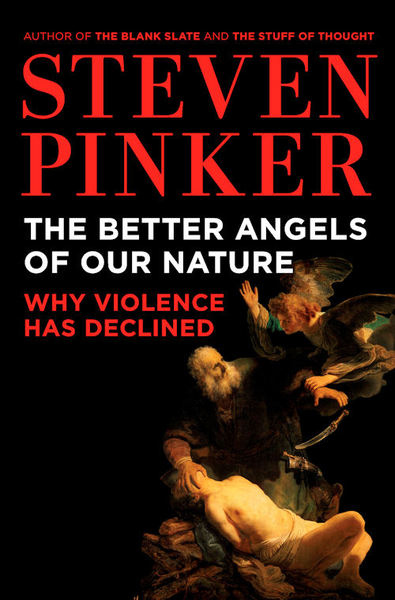

What typified Socratic dialectic was conceptual analysis and argumentation, while Pinker situates such inquiry in the context of our existing body of scientific knowledge. While Plato was a committed rationalist who argued for the view that knowledge is tied to an otherworldly realm of immaterial Forms, Pinker’s view of rationality is firmly rooted in empiricism. For example, public discourse should proceed in a way vaguely reminiscent of what we now call the Socratic method: Claims are subjected to careful examination, and, as Pinker asserts in a New York Times interview, “the person with the strongest position prevails.” In his new book, Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters, Harvard cognitive psychologist and linguist, Steven Pinker, focuses on ways a society can become corrupted, or less rational. For example, despite remarkable scientific achievements, many societies resist what seem to be practically self-evident truths anyone can uncover with a modicum of critical thinking skills. Since Plato’s time, events around the globe suggest the struggle between rationality and irrationality continues. One could argue that it was the collective irrationality of Athenian citizens that led to Socrates’s unjust demise. Charged, convicted, and executed for corrupting the youth and (what amounts to) atheism, Socrates’s activities made people uncomfortable enough to warrant killing him. Just consider what Athens’ democracy did to Plato’s beloved teacher, Socrates.

The results of this failure, he held, can be catastrophic.

In fact, Plato thought we are typically not rational enough to grasp what really is best for us. The problem, of course, is that we might very well be wrong.

Long ago, Plato argued that each of us does what we think is best for us.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)